Red Lodge Clay Center – Short-Term Resident 2012, (ASPN Mentor) 2015

Errol Willett is a member of the Ceramics Faculty at Syracuse University’s School of Art and Design and has lived in Fabius, NY since 1999. He served as Chair of Syracuse University’s Department of Art from 2009-2012. He has an MFA degree from Penn State University and undergraduate studies in art At CU-Boulder, Skidmore College and the University of Regensburg, Germany. He was a resident artist at the Anderson Ranch Art Center, Aspen, Colorado; the Peters Valley Craft Center in NW New Jersey; and the Banff Centre in Canada. Recent projects include the permanent installation, “Overlooked Information. The Carbon Espalier,” at the iSchool, Hinds Hall, Syracuse University; the exhibition “Affinity,” at the Incheon World Ceramic Centre, Incheon, Korea; “30 Teapots,” at the Baltimore Clayworks Gallery, Baltimore, Maryland; and the installation “Staying on Good Terms with Nature,” Everson Biennial, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY . Recent studio work has looked at the hubris of our instinct to control and organize nature; at Islamic patterns, Chinese grain baskets, hollowed-out wood bowls and glazes made from wood-ash.

My forms are often inspired by the parallel concerns of architecture and craft. Architecture often deals with inside/outside relationships, marrying the architect’s sculptural ideas with his/her concern for context and utility. The Egyptian pyramids and the earlier Ziggurat temples from the ancient near east are examples of this interplay between form and use. They also exhibit incredible creativity within the limitations of available, local materials.

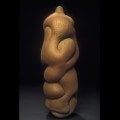

Spirals, rounded, swelling forms and rectilinear shapes juxtapose frequently in my work. The line or edge where a glaze meets raw clay and creates a mysterious depth or juxtaposes rough and smooth is a part of the vocabulary of ceramics that interests me.

I am most interested in the marks that become fundamental in creating structure. Some forms grow from one another organically and others meet in a relationship that creates tension. These relationships can be further clarified or made ambiguous.

In one body of work, I make wet line drawings around the surface of a soft cylinder of clay, pushing in on the lines until they become folds and the folds become structural. This drawing process sets up areas of weakness, which begin to collapse and transform the internal logic of the piece.

Two renegade architects whose work exhibit a profound relationship between form and structure, are Spaniard Antonio Gaudi and American Frank Gehry. Their work differs greatly due to the cultural contexts they were working out of – Gaudi as a Catalan in Nineteenth Century Spain and Gehry, a Jewish Canadian working in Twentieth Century Los Angeles. Both artists/architects however, show surprising similarities in their focus on the simultaneity of interior/exterior experience. Both challenge contemporary notions of design and both use structure as ornament.

Gaudi’s forms are biomorphic and often brightly colored while Gehry is starkly rectilinear and concerned with emphasizing the parts of the whole in chaotic juxtapositions. Gaudi’s forms represent both a spiritual fantasy world of dreams and myth, and a starkly vivid, tangible reality. They take you in and out of these opposing worlds, floating somewhere in between. In his work, much like Cezanne, Gaudi brought a fullness of form together with a fullness of color, both complementing nature. Gaudi came from a family of potters and from a tradition of exuberant Islamic-Catalan brick construction and tile decoration. His work exploits a potter’s approach to form in its plasticity, its swelling interwoven forms, and its tactile qualities. Gaudi was a genius in the use of light, volume, stone and curved lines, and in the marriage of his ideas with their surroundings.

In another body of work I have combined the traditions of Islamic repeating patterns and French espalier. The former is based on simple geometric relationships used to form complex patterns. It has been used to uplift the spirit through color and decoration and to make connections between the simplest observable geometric truths and the most complex mysteries of the world. French espalier, on the other hand, is the craft of training the branches of fruit trees to grow in specific repeating patterns.

Both traditions show the human instinct to control and organize nature. I am interested in how this instinct is impacting my art-making decisions as well as decisions of global import related to the environment, evolution, nuclear physics and the clash of science and religion.

Gehry blurs the boundaries between inside and outside with his corrugated cardboard and bentwood chairs and in many of his buildings. The American Center in Paris designed by Gehry uses a sliding glass entryway to make the distinction between inside and outside virtually invisible. On the mezzanine level of the American Center you look through a glass ceiling at the sculptural forms on the roof blending once again interior and exterior; allowing the inside structure to constantly interact with the outside.

Gehry’s overriding concern has been with the relationship of parts to a whole. His structures are a system of individuated elements, which acknowledge one another through form and materials but never blend into a seamless architectural complex. Describing the ideal chair Gehry talks about structure and surface completely integrated into a single unit–nothing is added.

“For me,” writes Gehry, “there was the one-room building. It was as close as I could get to that pure problem in which functional issues are so simple that you are faced with only the formal gesture.”

It is a very similar sensibility that leads me to manipulate the simplest hollow forms into ceramic vessels and to investigate the relationship of the parts of the structure I create to the whole.

The scale of my work ranges from the intimate to the human. The larger pieces heighten the difference between the life-size feeling and the intimate/tactile nature of the many rounded, swelling forms that make up the structure of the piece. The structure is flesh-like on the outside and skeletal on the inside. The forms refer to storage vessels, urns, bottles, and the human body.

In a series of flower vases I attempted to create a sense of the inside breathing or speaking through the outside. The basket form is interesting to me because it is both inside and outside. The focus is caught somewhere in between, at the rim which is tied together with the handle. This is a fertile metaphor for life–unifying internal and external experience through numerous bridges and connections.

The vase forms I am working on talk about inhaling and exhaling. Some are collapsing; others expanding; and the best seem to do both at once. I am inspired by the work of George Ohr and Hans Arp and the writer Anita Desai.

George Ohr’s pots twist and collapse exuberantly. Hans Arp’s Dadaist ‘concretions,’ like Gaudi, make allusions to nature and biomorphic forms and particularly interest me in the way they begin and end.

Indian writer Anita Desai in several novels creates characters who meet in the dance of the cobra and the mongoose; the expression of difference between thinking in the east and the west. The mongoose frantically circles its enemy, while the cobra waits patiently focusing all its energy for one single defensive strike.

“Our culture has consistently favored yang, or masculine, values and attitudes and has neglected their complementary yin, or feminine, counterparts,” writes Fritjof Capra in the Tao of Physics. “We have favored self-assertion over integration, analysis over synthesis, rational knowledge over intuitive wisdom, science over religion, competition over cooperation, expansion over conservation.”

It is interesting to me that the forms emerging in my work I find both in eastern mysticism and as products of twentieth century quantum theory. Neither the physicists who draw these primitive shapes as probabilities of atoms they cannot see, nor the eastern mystics who use these forms to celebrate ‘oneness,’ or even the ancient Mesopotamians who deified earth, water, sky and the four directions, completely understand the forms. According to Robert Oppenheimer, physicist and inventor of the atomic bomb, “what we are finding [in modern physics] is an exemplification, an encouragement, and a refinement of old wisdom.”

I am looking at modern architecture and also at the confusion in modern atomic physics over waves and particles–seemingly unrelated. Formerly, all life forms were broken down in physics to either waves or particles and behaved accordingly. Now at the atomic level scientists find basic life forms behave as both wave and particle simultaneously; Matter which appears to be in motion and at rest. These discoveries in physics show the fundamental structure of life as many things simultaneously. And for me form an intuitive link with the work of Guadi and Gehry.