Red Lodge Clay Center – Short-Term Resident (ASPN) 2019

Lillian Babcock grew up in Saint Paul, Minnesota where she gained an early appreciation of ceramics through her family’s daily use of their Warren Mackenzie stoneware. When her family moved to California, she participated in ceramic art programs at school, and knew early on that making pottery was something that held her interest. Though she intended to study international relations and Chinese language after living in Beijing for her senior year of high school, Babcock enrolled in a wheel-throwing class during her first term at California State University, Long Beach. She soon realized that ceramic art was her true passion. Babcock became a BFA ceramics major after working with CSULB professor Tony Marsh, who had trained with potter Tatsuzō Shimaoka, designated a Living National Treasure by the Japanese government. Additionally, she completed minor degrees in English Literature and Art History. Babcock has attended ceramics workshops at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, where she worked with artists Julia Galloway and Peter Pincus, both of whom have helped shape her artistic vision. Babcock plans to pursue an MFA degree in Ceramics.

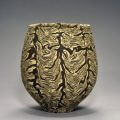

I am driven to make refined, elegant pottery that sparks happiness when used or seen. Handmade vessels are a manifestation of my own dreams and personality, and hold meaning that goes beyond pure appearance. The tactile way clay moves in my hands and the puzzling of patterns and colors on the ceramic surface is a continuous game with limitless options. Like people, vessels can be metaphorically described by their body parts; they can have a foot, belly, neck, shoulder, mouth, and lip. These human characteristics make pots very personal, and link the work with their owner or maker, especially when the pot is being used. Ceramic art brings beauty to our homes and reflects how we live and what we value. Pottery is an art form that rebels against single-use paper plates and mass-produced, uninspired tableware. It is both sustainable and unique. I believe that my instinctive drive to create beautiful, joyful, functional objects recalls age-old and familiar daily food rituals that satisfy body and soul.

German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Judgment, differentiated between free and dependent beauty—useful terminology when exploring the creative possibilities of craft. Free beauty requires no pre-conception of what qualities a work of art should possess, relying instead on the object’s sensory or emotional appeal. Essentially, “that which pleases without a concept.” Dependent beauty relies on conditioned or determinate concepts that define the perfection of a type. In the art world, objects described as having free beauty can be compromised by their dependence on function. As such, form and surface treatment should always be appreciated as part of a pure aesthetic. I would, however, judge the throwing of a good pot not just by how aesthetically pleasing it is, but on how close its form is to that of other successful pots—Kant’s idea of dependent beauty. If a teapot is elegant, but does not pour tea without dripping, it loses some of its function, and is inherently less beautiful. For me, its beauty is dependent on its capacity to function as a good pot.